Ziegfeld Follies, Ziegfeld Girls: Staging Provocative Beauty

A century ago, a line of women glide languidly into the glow of the footlights on a Broadway stage. Nearly nude, they shimmer with feathers, jewels, satin, and sequins. The audience watches in a spellbound mix of desire, envy, and awe.

Here, presented to the world as icons of feminine beauty, are the Ziegfeld Girls.

Ziegfeld Follies: Glamour as a Way of Life

Icons of Beauty and Spectacle

In early 20th-century America, the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway was a glittering realm of glamour and longing. Women were at the heart of the spectacle: an ever-changing roster of showgirls, dancers, and singers whom Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., presented as the ideal American woman. They were more than performers; they were offered as archetypes of beauty and modern femininity.

I want to explore who and what the Ziegfeld Girls were – focusing on their roles, status, and influence. Ziegfeld’s showgirls came to symbolize American glamour through meticulously curated image‑making and strategic commodification.

I’ll explore how this phenomenon established the them as the twentieth‑century beauty ideal. From genuinely talented stars to anonymous “ponies” in the chorus line, the Ziegfeld Girls personified both the opportunities and the contradictions for women in the Jazz Age.

Ziegfeld famously said he was “glorifying the American girl.” His Follies did exactly that. At a time when vaudeville offered plenty of pretty faces on stage, Ziegfeld set out to elevate his female performers to a new level. He paid big salaries, used glamour photography, and listed top talent by name in the program at a time when doing so was rare. Ziegfeld turned his performers into living symbols—women to be admired, desired, and objectified.

Ziegfeld’s Magic Beauty Dust

The Ziegfeld Follies began in 1907 and ran on Broadway until 1931, a year before Ziegfeld’s death. The show was periodically revived, with performances in 1934, 1936, 1943, and 1957.

Over the top: that was the Ziegfeld way. The most elaborate stage scenery, the most extravagant costumes, the best talent. And the most beautiful: Ziegfeld became known as a star-maker with an uncanny eye for feminine allure. His name became a trademark of quality; by the 1920s, the “Ziegfeld Girl” had become a guarantee of spectacle and style. Scores of young women crowded his office waiting rooms in hopes of being chosen. Once tagged with his brand, all doors opened. Becoming a Ziegfeld Girl meant getting sprinkled with a kind of magic beauty dust.

Ziegfeld cultivated an aura of glamour around his performers through careful publicity and myth-making. In the press, he was often portrayed as an arbiter of feminine beauty, passing judgment on who was worthy of his show. News articles stoked the public’s fascination with his selection process; he would speak at length about evaluating women in all aspects, including their hands and ankles. All of this was part of a calculated strategy: by making his performers seem extraordinary, Ziegfeld ensured his Follies productions carried a cachet beyond its skits and songs.

Crucially, Ziegfeld also took pains to put on shows that were considered classy, a cut above the bawdy girly shows and burlesque productions available elsewhere. At the same time, the shows never strayed from conventional forms of entertainment; there was no avant-garde experimentation, no subversive intent. This formula kept the Follies popular among the New York social elite as respectable entertainment.

Staging the Ideal Spectacle

Women as Performative Objects of Desire

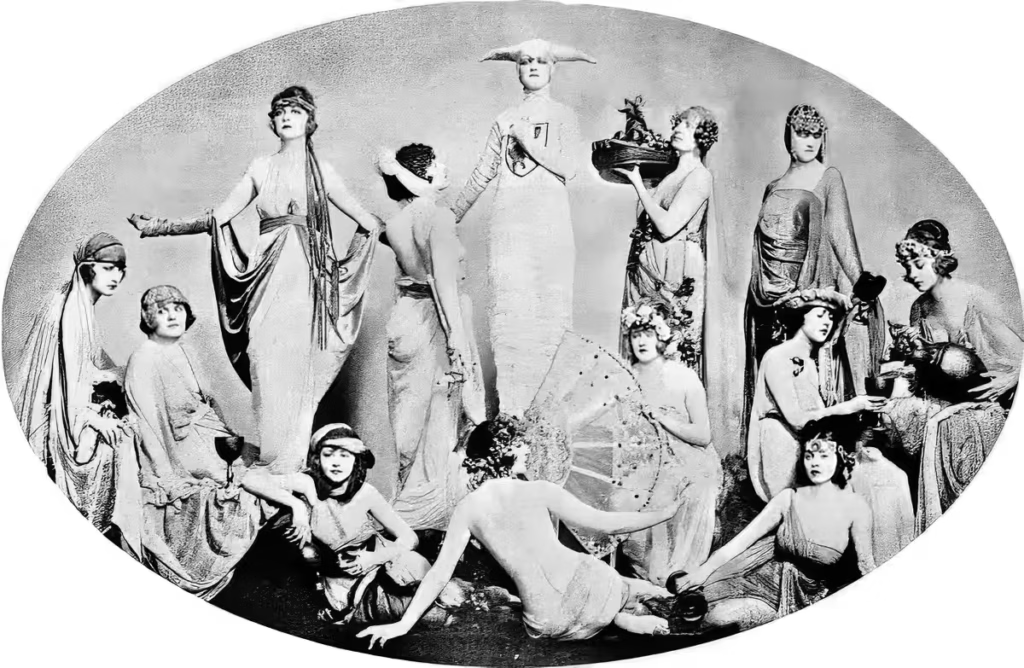

On stage, the Ziegfeld Girls were presented as living embodiments of an ideal. They often appeared in grand pageants or tableaux that blurred the line between performer and decoration. Gathered on stage, they made for show-stopping scenes that the Follies were famous for.

An example was the Follies of 1913, in which Ziegfeld Girls pretended to swim while a massive mock-up of the Panama Canal was unveiled center stage. Similar scenes were presented in the context of airplanes, battleships, and automobiles. These were brilliant mergers of feminine spectacle with patriotism and technological progress, building on an audience’s appreciation for all three.

One particular trope was used over and over again: that of Ziegfeld Girls as desired art objects. A 1912 number called “The Palace of Beauty” presented women as property of a sultan’s harem. “Creation,” part of the 1920 Follies, featured a woman posed mid-air, set to the song “They’re So Hard to Keep When They’re Beautiful;” this underscored the constructed nature of their appeal.

In 1926, “Treasures of the East” presented women in flesh-baring harem-inspired poses, transforming them into exoticized treasures. One performer appeared nearly nude, posed as an immobile “slave girl.” Ziegfeld cleverly exploited a legal loophole that allowed nudity on stage as long as the performers remained completely still—a tradition that evolved from the “tableaux vivants” (living pictures) popular in European art salons.

Ziegfeld Girl as Fashion Icon

Costuming was a key element of the Ziegfeld Girl image. Ziegfeld enlisted top fashion designers like Lady Duff Gordon to create extravagant gowns, headdresses, and lingerie for his productions. He also hired Duff-Gordon’s professional fashion models to strut the stage in her couture creations, effectively merging the worlds of high fashion and Broadway show.

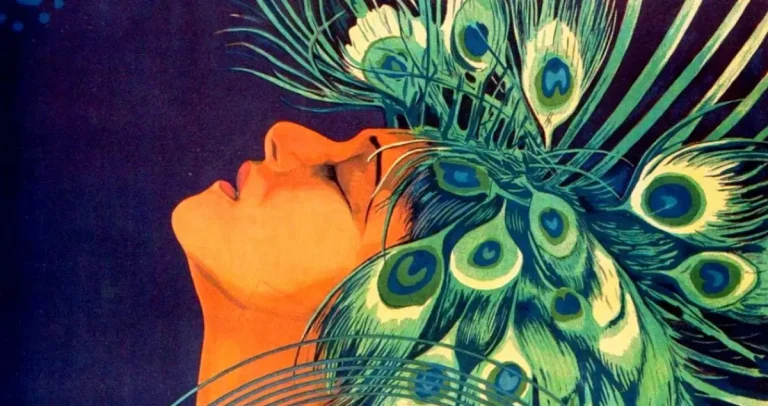

One celebrated model, known simply as Dolores (born Kathleen Mary Rose) became a Follies sensation not for her voice or dance moves, but for the way she showed off costumes. Draped in shimmering couture, she needed only to walk—slow, regal, and unsmiling—for the audience to believe they were witnessing the pinnacle of beauty. Her most legendary appearance came in a towering “peacock” costume, complete with a glittering train that fanned behind her like jeweled plumage, transforming her into a living emblem of opulence and artifice.

Ziegfeld styled himself as an architect of fashion—someone who could steer public taste from the stage. He wrote in the Ladies Home Journal that his productions “put the short skirt into everyday wear,” boasting that he deliberately selected the newest French designs to “break the ice” for their adoption by American consumers. By putting these styles in front of mass audiences, he turned theatrical spectacle into fashion marketing. One Fifth Avenue boutique manager supposedly told him she sold more dresses featured in the Follies than she ever could have on showroom mannequins.

But Ziegfeld went beyond seeing himself as an arbiter of fashion: he asserted a unique talent for putting the right clothes on his performers. “If all women were to be studied and had clothes selected for them with the same care that they are in the follies,” he wrote in the LHJ, “I think all women might appear to better advantage.”

This reciprocal relationship among stage, commerce, and society reinforced the Ziegfeld Girl as both a desired object and an aspirational figure. Audiences wanted to see her on stage and in photographs because she was presented as the epitome of beauty—styled, costumed, and posed to achieve the greatest possible allure. Ziegfeld’s careful construction of image made the Ziegfeld Girl not only a trendsetter but a symbol of elegance and desirability that extended well beyond the theater.

A Hierarchy of Talent

Stars, Showgirls, and Ponies

Beneath the plumes and rhinestones, who were the Ziegfeld Girls? In truth, they were a diverse ensemble of women – some big stars, others anonymous but indispensable. A few, like Ann Pennington, combined beauty with exceptional talent. Pennington was petite and vivacious whose spirited dancing (from toe-tapping soft-shoe to the latest jazz dances) made her a featured star of the Follies, as well as other Broadway shows and Hollywood films.

At the other end of the talent spectrum were performers like Lillian Lorraine and Olive Thomas, women whose allure lay chiefly in their looks. Lillian Lorraine was charming and beautiful–so much so that Ziegfeld fell in love with her offstage. Onstage, she wasn’t a strong singer or dancer; critics often noted she “could not act” to save her life. Yet in one Follies number, she famously rode a suspended gilded swing out over the audience, a vision in midair scattering flowers and smiles. Moments like that made her a crowd favorite regardless of vocal talent.

When Olive Thomas was asked to appear on Ziegfeld’s stage in 1916, she is reported to have said “I can’t act, I can’t sing, and I can’t dance.” None of that matters, she was allegedly told, and it didn’t. She was so beautiful that all she had to do was walk on stage. Thomas went on to become a silent film actress, her girlish image helping to define the silent-era ideal of feminine innocence.

The smaller and more agile dancers, nicknamed “ponies,” performed the fast-paced routines: tap dances, acrobatic numbers, and syncopated kick-lines that brought energy to the show. This division of labor by height and “type” was pioneered by Ziegfeld’s choreographer Ned Wayburn. The contrast made the Follies a feast for the eyes – a continuous flow from full-stage spectacle to lively variety, and back again.

Outsiders as Featured Insiders

One of the most intriguing aspects of Ziegfeld’s revues was how they included contrasting characters. Fanny Brice, a gifted comic and singer, created her own category of Ziegfeld Girl – one based on personality and wit rather than classical beauty. Brice, a Jewish woman from New York’s Lower East Side with a flair for Yiddish humor, hardly matched the idealized beauty of Ziegfeld’s typical showgirls. In Brice’s success lay a paradox: she proved that an “ugly duckling” could thrive in the gilded world as a counterpoint to the glittering showgirls.

Likewise, African American performers were rarely allowed into this fantasy realm, except in strictly controlled ways. The black comedian Bert Williams was a top-billed star in the 1910 Follies, but was forbidden to share the stage directly with the white chorus girls. The Ziegfeld Girls embodied a vision of all-American femininity that was, by the standards of the day, narrowly white and Christian; other kinds of performers were placed apart, used to spice up the program without disturbing the main image of idealized white womanhood. https://www.musicals101.com/ziegfollies.htm

Ziegfeld Follies as Launchpad for Fame

Nevertheless, for the women who did fit the Follies mold, Ziegfeld’s stage could be a launchpad to broader fame. Dozens of Ziegfeld alumnae became household names in the entertainment world. Silent film era icons like Louise Brooks, Marion Davies, and Billie Dove all started as Ziegfeld performers before Hollywood lured them away.

Those women who achieved fame as Ziegfeld Girls helped set a standard for glamour and beauty that stretched well beyond Broadway. Dazzling sister act the Dolly Sisters became emblematic of Jazz Age extravagance, both onstage and in their scandalous high-society life offstage. And Marilyn Miller, a golden-haired dancing star discovered in the Follies, captured the era’s imagination so completely that she became one of Broadway’s highest-paid leading ladies by the 1920s, reinforcing the notion that a Ziegfeld Girl could become the star of her generation.

Jazz Age Women: Allure and Ambivalence

Yes You Can, No You Can’t

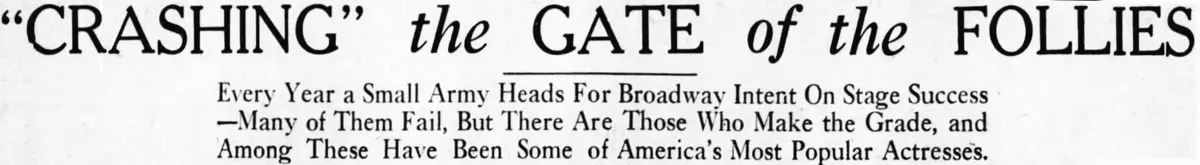

The rise of the Ziegfeld Girl coincided with the Jazz Age, a time of expanding freedoms and stark contradictions for women. On the surface, the Follies showcased women’s newfound opportunities: young, would-be chorus girls flocked to New York, hoping to earn their own income and bask in public admiration. Joining the Follies was seen as a liberating escape from small-town life and strict Victorian norms – a chance to dance, to travel, to be part of the most talked-about show in America. The image of the flapper showgirl – carefree, financially self-sufficient, decked in pearls and furs bought with her salary – became a popular fantasy of modern womanhood in the 1920s.

But the glamour had a darker edge. Ziegfeld Girls were celebrated, but also objectified and tightly controlled. Their value was tied to physical perfection, and maintaining that perfection could be difficult. The pressure to remain eternally youthful and beautiful led some down troubling paths. One tragic story was that of Allyn King, a Follies girl whose obsession with keeping slim (reportedly after Ziegfeld urged her to lose weight) spiraled into severe illness and depression; she ultimately died young, a cautionary tale of the industry’s exacting standards.

Others grappled with the ephemeral nature of their fame. A showgirl’s career typically lasted only a few seasons, leaving many women worried about their prospects as they aged out of the chorus.

Be Sexy On Stage, Careful Off

Relationships were another area of contradiction. The allure that made these performers stars also drew swarms of admirers, not all of them welcome. Wealthy stage-door suitors – nicknamed “Stage Door Johnnies” – lurked by the theaters, eager to give a Ziegfeld beauty gifts in exchange for dates.

Some Ziegfeld Girls did marry millionaires, their weddings dutifully reported in the society pages as real-life Cinderella stories. But just as often, the attention could be exploitive. Showgirls walked a fine line between leveraging their sexuality for advancement and becoming its victim.

The women had to be alluring on stage yet offstage they were expected to uphold a ladylike image and not jeopardize the Follies’ respectable veneer. This double standard meant that a Ziegfeld Girl’s personal life was often policed, even as Ziegfeld Evil Buffooneted a message of modern, liberated femininity. It was a delicate balancing act, and not everyone landed on the right side of it. The term “Ziegfeld Girl” ultimately came to symbolize a unique kind of Jazz Age woman – one who was at once empowered and constrained, exalted and exploited.

Ziegfeld Girl in Legend and Legacy

Movies Enshrine The Follies In Cultural Memory

Though the last Follies under Ziegfeld’s direction took the stage in 1931, the Ziegfeld Girl never faded from American culture. In the decades that followed, she lived on as an icon in numerous incarnations – through Hollywood films, periodic stage revivals, nostalgia for the lost glitter of Broadway’s heyday, and the ongoing lineage of showgirls in new venues.

In 1936, MGM released The Great Ziegfeld, a lavish biographical film that won the Academy Award for Best Picture. It dramatized Ziegfeld’s life and staged opulent recreations of Follies numbers, complete with hundreds of costumed girls twirling on colossal sets. The film introduced a new generation to the imagery of feathered headdresses and staircases full of smiling beauties.

Another MGM spectacle, Ziegfeld Girl, hit the screen in 1941, explicitly focusing on the lives of three fictional Follies performers. Its story followed the familiar arc – the discovery of a naive young woman, the intoxicating rise to fame, and the personal troubles behind the scenes – and ended with one Ziegfeld Girl tragically dying as a poignant reminder that the spotlight can burn as well as shine.

The movie cemented the term Ziegfeld Girl in the popular lexicon, supplanting the earlier phrase “Follies Girl.” It emblazoned the brand in public memory and helped turn the real Follies veterans into almost mythic figures. In one famous scene, actress Lana Turner (playing an ambitious showgirl) collapses on a grand staircase, surrounded by a human “wedding cake” of chorus girls – a piece of pure cinematic melodrama that nonetheless pays homage to the visual grandeur of the Ziegfeld Follies.

Beyond Film: Vegas Showgirls

The essence of the Ziegfeld Girl found new life in the evolving institution of the American showgirl. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Las Vegas. From the 1950s onward, Vegas production shows unabashedly modeled their routines on the Ziegfeld formula: monumental staircases, glittering barely-there costumes, and a chorus line of statuesque, high-kicking beauties. The Vegas showgirl—often topless but draped in jewels and plumage—became a kind of exaggerated echo of the Ziegfeld Girl, trading the original’s innocence for overt sensuality but keeping the feathers and fantasy intact.

Even as Las Vegas in the 21st century shifted toward family-friendly attractions, the classic showgirl revues persisted as a nostalgic draw, a throwback to “old fashioned Vegas” glamour alongside the neon and slot machines. The enduring presence of showgirls in popular entertainment attests to the lasting power of the template Ziegfeld created. From Radio City’s Rockettes (who carry on the precision kick-line tradition) to modern Broadway revivals that celebrate the art of the chorus line, the DNA of the Ziegfeld Girls is still very much in circulation.

Ziegfeld Girl as Cultural Reference Point

The Ziegfeld Girl remains a touchstone–a shorthand for a certain vision of feminine glamour. She exists in the collective imagination as the glittering archetype of the Golden Age of Broadway. Over time she has been variously romanticized, satirized, and reinterpreted.

In the 1960s musical Funny Girl, a dramatization of Fanny Brice’s life, there’s a telling moment when Brice (played by Barbra Streisand) finally joins the Follies. She looks around at the leggy, elegant chorus and instantly recognizes both the honor of the title Ziegfeld Girl and her comic incongruity in that line-up. The scene cleverly highlights what had become obvious by mid-century: to be a Ziegfeld Girl was to be an icon of beauty, part of an exclusive club that even other talented performers regarded with a mix of awe and irony.

The 1991 play Ziegfeld: A Night at the Follies, was a musical extravaganza meant to recreate the show’s glorified heights, including its cultural impact. “It’s 1927, and every girl dreams of being a Ziegfeld Girl,” one character announces early in the show. The play’s author credited Ziegfeld’s mystique as so strong that “every girl wanted to work for Ziegfeld” and “every guy wanted to meet a Ziegfeld Girl.” . Arguably, one could say that as an idealized image, the Ziegfeld Girl retains similar influence today.

Outside of show business, the image also endures. Vintage photographs of Ziegfeld Girls (often nude studies) by Alfred Cheney Johnston and others continue to fascinate collectors and museum-goers, reminding us how the standards of beauty and entertainment were set a century ago.

Lasting Legacy of the Showgirl

In examining the legacy of the Ziegfeld Girls, I see more than sequins and feathers; I see a reflection of 20th-century America’s evolving ideals of womanhood. These performers were powerful symbols of race, sexuality, class, and consumer culture rolled into one. As icons, they helped materialize history on the stage—showcasing, for instance, the tensions between traditional femininity and modern independence, or between inclusive national pride and exclusive beauty standards.

Scores of real women performed in the Ziegfeld Follies, each with her own story, yet collectively they became a single legend that has far outlived any one of them. The Ziegfeld Girls defined an era’s look and dreams, and in turn, that era cast them into legend.

To this day, whenever we evoke the glamour of a bygone time, such as the flutter of a fan of ostrich plumes, the sparkle of a beaded gown under stage lights, we are remembering the Ziegfeld Girl. She remains, even now, the ultimate emblem of American stage glamour, a figure who started as a marketing idea in Florenz Ziegfeld’s mind and ended up an enduring icon of beauty and feminine allure.

I consulted the following books for this post:

- Brideson, Cynthia, and Sara Brideson. Ziegfeld and His Follies: A Biography of Broadway’s Greatest Producer. Screen Classics. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2015.

- Earle, Marcelle, and Arthur Homme. Midnight Frolic: A Ziegfeld Girl’s True Story. Basking Ridge, N.J: Twin Oaks Pub. Co, 1999.

- Farnsworth, M. The Ziegfeld Follies. Bonanza Books, 1956.

- Hanson, Nils. Lillian Lorraine: The Life and Times of a Ziegfeld Diva. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 2011.

- Mizejewski, Linda. Ziegfeld Girl: Image and Icon in Culture and Cinema. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.