Adorée Villany and Scandalous Naked Dances

Revised April 22, 2025.

Adorée Villany: Naked Enigma

Adopting the Dance of the Seven Veils

Adorée Villany tested the European limits on how much skin a dancer could show on stage during the early 20th century. She also pushed the boundaries of early modern dance choreography.

Most of all, she was an enigma. Adorée (or Viola) Villany was either French (born in Rouen), Hungarian (“The Pearl of the Puszta”), or a German Jew (born in Danzig as Erna Reich). She mostly performed in Germany, where she was variously known as a “barefoot dancer” (barfuß tänzerin) or “naked dancer” (nackttänzerin).

Most of all, she was an enigma. Adorée (or Viola) Villany was either French (born in Rouen), Hungarian (“The Pearl of the Puszta”), or a German Jew (born in Danzig as Erna Reich). She mostly performed in Germany, where she was variously known as a “barefoot dancer” (barfuß tänzerin) or “naked dancer” (nackttänzerin).

The Grazer Volksblatt states she began performing in the Berlin Überbrettl cabaret (perhaps in 1902) as “a[n Isadora] Duncan imitator.” She may first have come to public notice in 1905, performing the Dance of the Seven Veils (and presumably disrobing) while simultaneously speaking Salome’s final monologue from Wilde’s play.

In 1911, Munich police arrested Villany for indecent exposure after various exotic dances, including one as Salome. Villany defended herself as a “reform dancer,” claiming “my unveiled body reveals my soul.” Various artists came to her defense, and a jury acquitted her based on “the higher interests of art.”

Villany wrote that hers was the only authentic Dance of the Seven Veils, as she performed it “as Oscar Wilde imagined.” She denounced other interpretations as “tame Salome dancers” who showed “thoughtless movement” by confining “their emotions into squiggly pirouettes.”

Villany appears to have capitalized on the Salomania dance craze, and appeared quite often in the German press from about 1911 to 1914.

Appears in Two Films

In 1906 (some report a first version in 1902), Villany appeared in Tanz der Salome, a short by pioneering German director Oskar Messter. Messter was one of the first to experiment with matching sound to film, and Tanz features a semi-nude Villany dancing and singing. A modern critic of the film writes:

Dance of Salomé draws upon a fin‑de‑siècle male fantasy familiar from Oscar Wilde’s drama, Richard Strauss’s opera, and the paintings of Gustave Moreau. In Salomé’s image, the excluded Other—nature, sexuality, the feminine—returns both as seduction and as threat… blending striptease with opera, the woman before the camera transcends the boundaries of both genres.

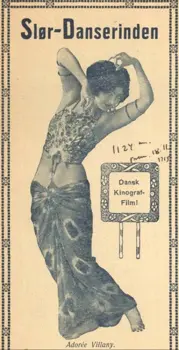

Villany also appeared in director Rino Lupo’s 1915 Danish silent film Slør-Danserinden (The Veil Dancer), which has a Salome-like theme. The program noted that she was “popularly called ‘the bare dancer’” and that the film features “art-reform-dance.” Villany reportedly lived in Scandinavia at the time while performing at popular cultural institutions and circuses.

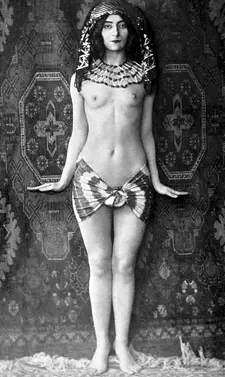

A Serious Book With Nude Photos

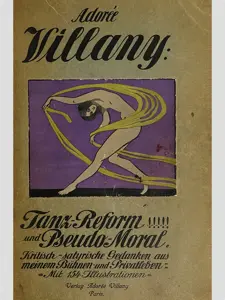

While Villany remains somewhat obscure, she did leave behind a fascinating book with illustrations of herself, many nude or semi-nude, in dance poses. The book, published in German in 1912/1913 as Tanz-Reform und Pseudo-Moral; kritisch-satyrische Gedanken aus meinem Bühnen- und Privatleben (Dance Reform and Pseudo-Morality—Critical-Satirical Thoughts from My Stage and Private Life) outlines her ideas about dance in some detail.

Villany was part of the German Dance Reform movement—also known as Ausdruckstanz or expressionist dance, an artistic and social movement in Germany during the early 20th century. It emerged as a reaction against the rigid forms and conventions of traditional ballet, aiming to express individual emotions and experiences through dance. The movement was deeply intertwined with the broader Lebensreform movement, which sought to reform various aspects of life, including art, physical culture, and social values.

In the early 1900s, Germany was the crucible for Ausdruckstanz, where Clotilde von Derp, Mary Wigman, and Grete Wiesenthal forged new movement vocabularies that laid the groundwork for modern dance. At the same time, American pioneers Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis were touring European cultural centers—bringing Greek‑ and Indian‑inspired solos to German audiences—while Canadian Maud Allan conceived her Vision of Salome in Berlin around 1906 and then sparked Salomania in London in 1908.

It is difficult to know how Villany fit in with these other dancers and to what degree who inspired who to do what. Dance historians tend to regard Villany as a minor figure who courted controversy (and publicity) for performing in minimal clothing. And, unlike the other dancers mentioned above, she didn’t establish a school or teach students. Yet she claimed to be rigorous in her work, committed to “reform of dance and bodily expression … pursued with artistic seriousness.” Villany draw inspiration from the ancient East—regions including India, Greece, and North Africa—to present a new form of dance.

A Solo Dance Revolution

Dance Reform and Pseudo-Morality is both a choreographic treatise and a defiant rejection of early 20th century moral censors. Villany opens by declaring her mission: to overthrow the prevailing ballet orthodoxy with its “hackneyed flourishes and perfunctory footwork.” In its place she wanted to establish a body‑as‑art ideal that communicates directly through form as emotion rather than form for form’s sake.

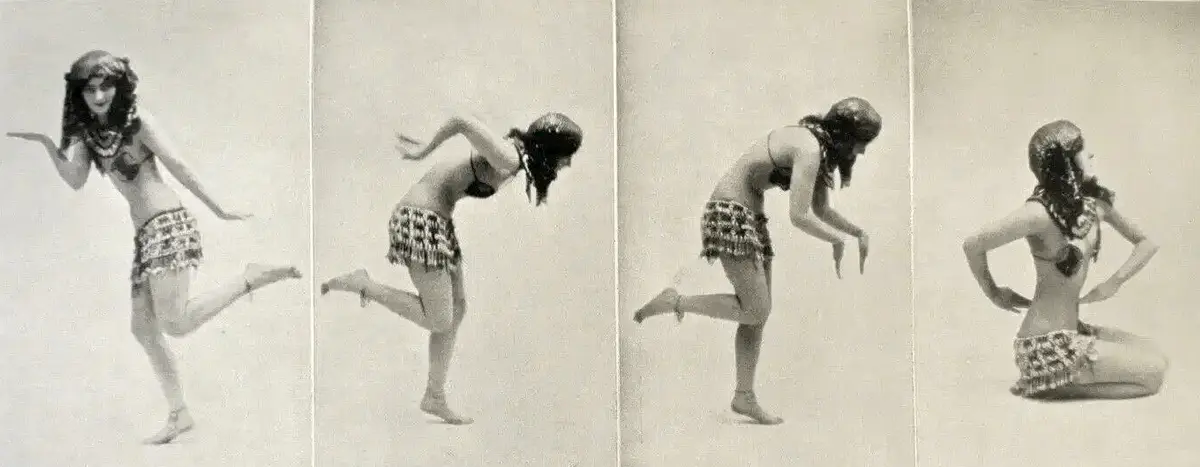

In the first two‑thirds of the book, Villany offers a meticulous, dance‑by‑dance analysis of her so‑called “stilisierten Tänze” (“stylized dances”). Each chapter presents the emotions behind a dance and explains how to use precise arm movements, torso alignments, and facial gestures forge an emotional bond with the audience. To underscore her points, she uses many captioned plates of “mimisch‑plastische Akte” (expressive, sculptural gestures) intended to illustrate the dance.

Villany frames her work explicitly as “a sweeping revolution of the solo dance form,” critiquing ballet’s regimented technique. Through practical exercises and costume innovations—flowing drapery, barefoot practice, streamlined silhouettes, and nudity—she demonstrates how dancers can shed acrobatic drill and embrace pure expressive movement.

By fusing detailed theoretical essays with photographic documentation, Dance Reform and Pseudo‑Morality is very useful for tracing the birth of modern dance. It captures the avant‑garde impulse to rebel against classical ballet’s constraints and to invent a new choreographic language of gesture, emotion, and individual artistry.

What Happened to Adorée Villany?

Advertisements for Villany performances appear in the German press until 1927. The last I was able to find was for an appearance at the Hotel Westfalenhof, where she was billed as “the international dancer… [who] has previously performed on the grandest stages of Europe.”

Also in 1927, the German dance critic Werner Suhr mentioned her in his book Der Nackte Tanz (The Naked Dance). Suhr gives Villany credit for her daring nude dances and censorship battles in Munich (1911) and Paris (1913), but is less than complementary about how she ended up.

Today, Villany performs in a second-rate cabaret on the Kurfürstendamm. Hardly anyone pays serious attention anymore. Provincials and pious capitalists watch in amazement as a somewhat aged woman, unnecessarily undressed, takes the stage. The great scandals are long forgotten… Anyone who sees the now-theatrical, poorly made-up dancer today can scarcely understand the passionate praise once given to her.

Nothing more seems to have been heard from her after that point. She may have lived on afterwards, perhaps in Berlin or elsewhere in Germany or some other nation.