The Ziegfeld Follies: Revolutionizing Broadway, Hollywood, and Culture

The Ziegfeld Follies changed American entertainment in a big way. When Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., introduced the Follies of 1907 at the New York Theatre on Broadway, he took spectacle to a whole new level.

It started as an uncertain experiment. It blossomed into an entertainment empire that ran until 1931 (with periodic revivals after Ziegfeld’s death in 1932). Along the way, the shows influenced everything from Broadway musicals to Hollywood films.

The Follies were more than just entertainment, just a night out. They were cultural events that changed how people thought about romance, beauty, and propriety.

From Vaudeville to High-Class Spectacle

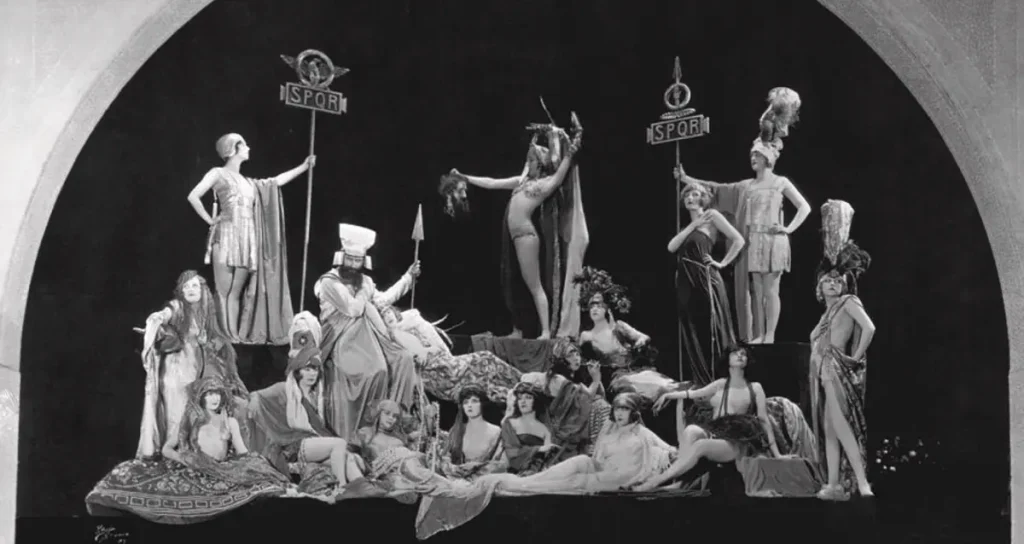

Before Ziegfeld, vaudeville variety shows were loose collections of singing, dancing, comedy, and pretty girls, often thrown together with widely varying talent. It was fun, but it lacked polish and prestige.

Vaudeville was regarded as middlebrow entertainment, something that didn’t offend but also didn’t aspire to much beyond some oohs and ahhs or few laughs. The shows were also modest, with limited stage sets and costumes that weren’t especially exciting.

Ziegfeld changed the game. He knew that audiences wanted more—more star-power, more extravaganza, more class. And, of course, beauty. Beauty presented beautifully.

People also wanted to see something modern. Early twentieth century New York City was pulsing with change—cars, electricity, skyscrapers were all new. There was talk of the “new woman,” females who dared think of a life outside the home. The time was ripe for a show with a current take on all the innovation that was upending decades of convention.

Ziegfeld was canny enough to understand all this. The result? A show with first-class comedy, music, dance, and stunning visuals. People saw his Follies as more sophisticated than vaudeville, with a greater sense of style and modernity.

London and Paris, then New York

Ziegfeld went to London in 1894. While there, he saw how much audiences loved musical comedies with beautiful women dressed in fancy, immodest costumes. Anna Held was one such performer, and her act was charmingly filled with sexual innuendo. Ziegfeld wanted to bring that kind of style to America. He convinced Held to come back to New York with him.

Ziegfeld aimed to make her a star by any means, including making up stories that were catnip to the press. One such tale claimed that she took a milk bath every day to make her skin supple and creamy. He even staged a confrontation with a milkman in front of reporters, claiming a delivery was sour. The free publicity put Held in the spotlight and helped propel her to musical comedy stardom. But after a decade of success, it was time for something new. Held suggested a variety-style revue like the Folies Bergère in Paris. Ziegfeld loved the idea.

When the first Follies launched in 1907, Ziegfeld was so uncertain of its success that he left his name off the title. But as soon as it became a hit, that hesitation disappeared. The show became the Ziegfeld Follies, and each year it became splashier and more spectacular.

A Star-Making Machine

The Follies launched many performers from obscurity to stardom. W.C. Fields went from vaudeville juggler hugely popular comedian. Will Rogers was a “cowboy performer” who became a nationally beloved storyteller. Eddie Cantor began as a singing waiter and became a Broadway and movie headliner. Bert Williams started as a minstrel performer and became one of the first Black entertainment stars.

Even among these famous men, it was the women who stood out in the Follies. To name just a few: Fanny Brice was a world-renowned comedian; Ann Pennington was the most talented dancer on Broadway; Ruth Etting had over sixty hit records; Ina Claire starred in over twenty Broadway productions and a dozen films; Marilyn Miller was Broadway’s brightest musical star; Louise Brooks went on to become a legendary actress and writer.

By the time of his death, Ziegfeld was revered as a star-maker, someone who could work a special magic. He was “a double-doored institution,” wrote the Oakland Post Enquirer in his obituary. “Through the back entrance swarmed a horde of waitresses, telephone operators, stenographers, obscure vaudeville artists, factory girls, co-eds. They emerged [from the front door] with names spelled in electric bulbs.”

The Ziegfeld Girls: Icons of Beauty and Allure

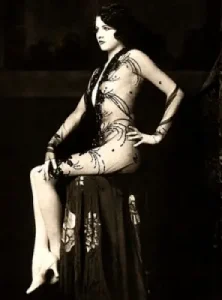

Ziegfeld knew how to pick beautiful women for his shows. He selected a special few as showgirls—women who were so attractive and charismatic that spectators couldn’t take their eyes off them.

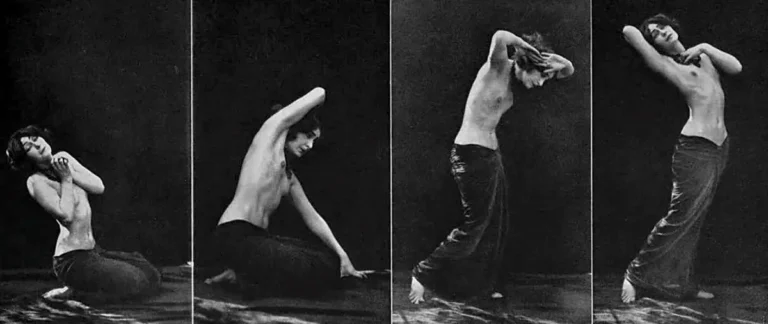

They wore fantastical, provocative costumes and trained in “The Ziegfeld Walk”—a slow, deliberate strut designed to show them off. Audiences were entranced. The women quickly became cultural icons: the Ziegfeld Girls.

The media fueled their legend. Newspapers called Ziegfeld “the acknowledged arbiter of American beauty,” and the San Francisco Examiner raved: “Out of America’s vast garden of girls, Ziegfeld picks the perfect blossoms. The Follies Girl stands throughout the world as the synonym for sheer loveliness, daintiness, charm, and allure.“

Ziegfeld, the Master of Hype

Ziegfeld wasn’t just a producer—he was a marketing mastermind. As a young sideshow operator, he once sold tickets to see an empty water tank, claiming it contained invisible fish. That same knack for spectacle and illusion shaped the Follies.

He fabricated stories to make his Follies stars seem even more interesting. Ziegfeld claimed the star of the first Follies, Nora Bayes, lived on nothing but lollipops to keep her figure trim. Although Fanny Brice was already an established vaudeville performer before the Follies, Ziegfeld claimed he discovered her “hawking newspapers beneath the Brooklyn Bridge.” He also told the press he insured showgirl Hilda Ferguson’s limbs for $100,000.

Every year, he promised bigger, flashier productions than the last. He invented glamour photography, hiring photographers to take carefully posed, risqué portraits of his performers. These images were widely published, fueling the fantasy that Follies Girls were the most beautiful women in the world.

A Visionary Producer, Tastemaker, and Moral Influence

Ziegfeld knew how to mix comedy, dance, and spectacle. And Music. Irving Berlin, Victor Herbert, and George Gershwin wrote for the Follies, and they gave it the latest sounds: blues, ragtime, and Tin Pan Alley. Jazz appeared early in the shows, helping bring it into the mainstream.

He also revolutionized stage design, hiring Viennese architect Joseph Urban in 1915. Urban’s lavish, color-rich set designs transformed the Follies into visual masterpieces. One critic later said that “Urban did more than any other man to revolutionize American stage design, revitalizing Broadway and influencing everything from architecture to industrial design.“

Labeling Ziegfeld “an institution” and “the greatest moral influence in the city,” The New Yorker in 1925 went on to say that “New Yorkers [don’t] go to the Follies to be entertained . . . They go there to worship—and to discover where the exact limit of propriety has moved.”

Pioneering the Nightclub Experience

The Follies shows typically ended around mid-evening. Ziegfeld guessed that audiences wanted the entertainment to last. He was right. In 1915, he launched the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic on the rooftop of the New Amsterdam Theatre. It was an instant success.

It launched the modern nightclub experience, with acts that were bawdier than regular shows. The women performers were dressed even more provocatively. Some stood on a glass runway above the audience, allowing audience members below to look up at their costumes from underneath, adding to the show’s erotic appeal.

Also new was having performers interact with the audience. Early Frolics featured “Balloon Girls” who had inflated balloons as part of their costumes. The performers would venture into the crowd and men were encouraged to pop the balloons with their lighted cigars.

The Frolic ran past midnight, which was rare at the time. The audience was often made up of high-society types, who were seen as sophisticated and “in the know” for attending an exclusive event and staying up late.

The Follies Go Hollywood

Hollywood saw Ziegfeld’s success and wanted a piece of it. By the late 1910s, film studios began signing Follies headliners.

W.C. Fields, Will Rogers, and Eddie Cantor became major film stars. But it was the Ziegfeld Girls that Hollywood desired the most. Many became silver screen icons, including Barbara Stanwyck, Louise Brooks, Marion Davies, and Olive Thomas.

More than just stealing talent, Hollywood borrowed Ziegfeld’s marketing techniques. His carefully curated “Glorified Girls” and “American Venuses” laid the foundation for the Hollywood star system, where actresses were carefully styled and marketed as idealized celebrities.

The Lasting Cultural Impact of the Follies

The Broadway musical as we know it began with Ziegfeld. He demonstrated that big, lavish productions with high-quality singing and dancing would draw big box office. The Follies also laid the groundwork for celebrity culture, with performers receiving huge amounts of publicity and public attention.

The Ziegfeld Follies left a legacy beyond entertainment. The shows launched celebrity culture by encouraging regular people to idolize glamorized performers. Ziegfeld Girls were held up to the public as the feminine ideal: how women should look, what they should wear, and how they should behave. In this way the Follies blurred the line between advertising, consumer culture, and gender role models.

The Ziegfeld Girls ideal offered a dual idea of perfection. On one hand, it was all about appearance, with the showgirl setting the (perhaps impossible) standard. On the other, the Ziegfeld Girl was an example of an independent woman, someone with her own identity and earning power.

The Follies are long gone, but their influence on entertainment, celebrity culture, and beauty standards remains.