Nyota Inyoka: Sensational Theatrical Dance and Artistic Performance

Nyota Inyoka (1896–1971), a French-born dancer and choreographer of European and possibly Indian or North African heritage, rose to prominence during a period when stylized fantasies of the East dominated Western stages.

Nyota Inyoka Rediscovered

Famous Female Dancer Falls into Obscurity

Although widely acclaimed during the 1910s and 1920s for her striking performances and scholarly approach to dance, Inyoka faded into obscurity by the time of her death in 1971. Absent from many standard histories of twentieth-century European dance, she is often reduced to a fleeting mention—one among numerous so-called “Oriental” dancers populating early modern stages.

Although widely acclaimed during the 1910s and 1920s for her striking performances and scholarly approach to dance, Inyoka faded into obscurity by the time of her death in 1971. Absent from many standard histories of twentieth-century European dance, she is often reduced to a fleeting mention—one among numerous so-called “Oriental” dancers populating early modern stages.

A Reputation Restored

Inyoka’s work is receiving renewed scholarly attention, with researchers revisiting her choreography, theoretical writings, and archival traces to reassess her artistic contributions—long marginalized yet deeply innovative—within the broader context of dance history and postcolonial critique.

The Allure of the East on Stage

Salomania and the Dance of the Seven Veils

As Edward Said has observed, Western imaginings of the “Orient”—a loosely defined region spanning India and North Africa to the Middle East and East Asia—often reduced the region to a theatrical vision of mystery, sensuality, and decadence. These fantasies, shaped by colonial ambition and artistic license, proved commercially potent. Theaters, cabarets, and music halls across Europe and America seized the opportunity, offering audiences a stream of “exotic” performances that bore little resemblance to the cultures they claimed to represent.

As Edward Said has observed, Western imaginings of the “Orient”—a loosely defined region spanning India and North Africa to the Middle East and East Asia—often reduced the region to a theatrical vision of mystery, sensuality, and decadence. These fantasies, shaped by colonial ambition and artistic license, proved commercially potent. Theaters, cabarets, and music halls across Europe and America seized the opportunity, offering audiences a stream of “exotic” performances that bore little resemblance to the cultures they claimed to represent.

Among the most visible expressions of this trend was Salomania—a wave of Salome-inspired dance acts that surged in popularity in the early 20th century. Loosely drawn from various sources, these performances replaced narrative complexity with erotic spectacle. The figure of Salome, unmoored from religious or cultural context, was recast as a fantasy of Eastern sensuality—a seductive presence designed to provoke colonial-era audiences while also conforming to expected notions of far away lands.

Oriental Dance and Performance Fantasies

This mode of performance reflected a larger sweep of Western curiosity and desire. The appeal of the East lay not simply in its visual richness, but in the license it granted artists to imagine a world of sensual decadence. Within this framework, performers like Inyoka occupied a precarious space: invited to embody the exotic, yet striving to imbue their work with spiritual intention, scholarly rigor, and artistic autonomy.

Watch the 1m video: Re-enactment of Inyoka’s dance Nagui.

Stage Persona and Crafting a Mythic Self

Real Identity vs. Reinvention

Official records list Inyoka’s birth as Aïda Étiennette Guignard, daughter of Mélanie Guignard—a Parisian schoolteacher or domestic worker—and an unnamed non-European father. But Inyoka would go on to rewrite her origins into something far more mysterious. She imagined a legacy steeped in Eastern spirituality and approached this vision with scholarly seriousness. Though her ancestry may have remained unclear, her artistic identity was anything but: it was methodically crafted, purposefully enigmatic.

The Serpent and the Star

According to Inyoka, her name was conferred by Swahili priests—Nyota meaning “star,” Inyoka meaning “serpent”—a symbolic mantle she wore with purpose. She said she hoped to live in a way “pleasing to the Gods,” and her career became an enactment of that vow. The name, and the public value she associated with it, was a key element of Inyoka’s self-invention as an entertainer and an artist.

Sacred Dance and Stage Show

Sacred Dance and Stage Show

Art Dance, Fantasy Dance

Inyoka navigated between meeting Western expectations and fulfilling her artistic desire to express the sacred myths of the East through dance. She was a performer who mixed theatrical mystery with scholarly intent. Inyoka leaned into dominant ideas about the “exotic Orient,” but not passively. Rather, she adapted the fantasy to fit her own ends, positioning herself as an emissary of ancient wisdom—an Egyptian priestess, an Indian mystic, a Cambodian temple dancer. Her performances weren’t simple spectacles; they were meant to be rituals, grounded in research and radiant with spiritual devotion.

Artistic Vision Rather Than Restoration

Inyoka’s dances were not restorations in the archaeological sense. She called them “reconstitutions,” speculative reconstructions based on study and artistic intuition. She drew inspiration from sculpture and ancient texts. To a French public primed to consume the Orient as decorative fantasy, Inyoka offered something richer: dance as a transformational rite. Her art evoked what audiences expected—sensuality, mystery, allure—but also offered her own deeply felt visions of truth and beauty.

Cultural Innovation and New Ways of Seeing

Part of what makes Inyoka remarkable is that she was of mixed heritage and, quite literally, embodied more than one culture. But in navigating between them, she didn’t simply blend traditions—she created something new. Her choreography didn’t just reflect her background; it offered a kind of cultural invention. Some scholars connect this to the idea of a performative créolité—not as a mixture of existing elements, but as something entirely original.

Magical Power

During her time, some recognized her as a unique performer. The renowned scholar of India Sylvain Lévi wrote of her in 1929:

A reconstitution? An evocation? A resurrection? A triumph of art? A triumph of science? A creation? Yes, all that and even more. The hieratic poses, the noble attitudes, the effusive fantasies, the solemn and graceful gestures that the learned eye takes time to contemplate captured in stone or clay, like fossil imprints of a beautiful unnoticed humanity, Nyota Inyoka animates them with her powerful Magic.

Famous Female Dancers in A Similar Space

Ruth St. Denis, Sent M’Ahesa, and Maud Allan

In some ways, Inyoka followed a path similar to Ruth St. Denis and Sent M’Ahesa (Else von Carlberg), and Maud Allan, Western white women who created performances inspired by their ideas of the Orient, often while adopting fictional stage identities. All three drew on ancient Egypt and other imagined pasts, turning cultural fantasy into modern dance. They shared an interest in using movement to explore mystery, beauty, and the distant past.

In some ways, Inyoka followed a path similar to Ruth St. Denis and Sent M’Ahesa (Else von Carlberg), and Maud Allan, Western white women who created performances inspired by their ideas of the Orient, often while adopting fictional stage identities. All three drew on ancient Egypt and other imagined pasts, turning cultural fantasy into modern dance. They shared an interest in using movement to explore mystery, beauty, and the distant past.

St. Denis brought a devotional spirit to her work, blending emotion with the rich aesthetic of her movements. Her dances offered Western audiences a charismatic journey into an imagined version of ancient Indian truths. She developed a dance style centered on flowing arms, expressive hands, and deliberate pacing. She often combined stylized poses with richly textured costuming to heighten visual effect.

Sent M’Ahesa, by contrast, developed a cool, precise style shaped by her studies in Egyptology. Her dances often looked like moving sculptures—still, formal, deliberate. She constructed her performances as carefully composed visual arrangements, using restrained gesture to evoke a sense of timeless ceremony.

Maud Allan embraced the sensual and visionary, presenting dances that shimmered with theatrical intensity. Her signature work, The Vision of Salomé, drew on symbolist art and fin-de-siècle decadence. Draped in pearls and veils, she embodied a femme fatale whose mystery lay not only in movement but in the imagined ancient worlds she seemed to conjure. Her performances were emotionally charged and physically radiant—designed to stir awe, fascination, and a touch of transgressive thrill.

Innovative Dance

But something different shaped Inyoka. While St. Denis and M’Ahesa worked as European women portraying other cultures, Inyoka was a woman of color living in an imperialist society. Audiences didn’t just see her as a performer of the “exotic”—they saw her as truly Other. That perception gave Inyoka’s performances a different weight; her work was often seen as more “authentic.” She used this perception carefully, creating dances that were mysterious and foreign-seeming, but true to her artistic spirit.

Folies-Bergère to Vishnu

Paul Poiret, Costume Couture, and Paris

In 1917, Inyoka debuted at the Folies-Bergère, billed as “Nioka-Nioka, the Pearl of Asia.” Early press celebrated her “exotic charm.” Her connection with the influential couturier Paul Poiret provided early opportunities. Poiret provided her with rich silk brocade outfits accented with exotic pearls and jewels.

He featured her in performances at his private Théâtre de l’Oasis in 1921, where she performed in costumes he designed. Poiret later claimed to have “launched” her career, along with other Eastern dancers. But Inyoka had already been performing for several years before she worked with Poiret, and her relationship with him did not last.

Dance Vision of Vishnu at Sea

A pivotal moment, according to Inyoka’s own narrative, came during a voyage with her husband, the Polish-French banker and collector André Krajewski, whom she married in 1919. On the journey home from Tahiti in 1921, she claimed a divine revelation: a vision of the Hindu god Vishnu dancing in golden splendor.

I saw a God in golden splendor on his pedestal, executing an extraordinary dance while sitting, with marvelous gestures of his arms and hands, accompanied by reptile-like movements of his torso.… It was a ray of light, as though it were an order from above. All my cloudy projects became clear in front of this obsession: to create Vishnu, to dance Vishnu, to incarnate Vishnu.

Overcoming Personal Tragedy and Career Success

Krajewski committed suicide later in 1921 over financial troubles. Despite this, Inyoka’s career gained momentum, especially with her inspired dance tribute to Vishnu. She performed at the prestigious Salon d’Automne in 1921 and toured extensively.

Ziegfeld Follies Look to A Woman of Color

Ziegfeld Girl?

Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., impresario of the Ziegfeld Follies, visited Paris in 1922, saw Inyoka perform, and wanted her on his stage. Newspapers started buzzing with claims that Ziegfeld had “discovered” “Princess Nyota Nyoka” in Paris. Ziegfeld is quoted in The New York Age, a leading Black newspaper, as calling her “mighty dark” and stating that he planned to put “her in the [Ziegfeld] Follies as soon as she arrives in New York.”

The newspaper hailed Ziegfeld for having the courage to put her on stage without the need for her “‘pass for white’ as we have known colored girls of light complexion to do in order to hold membership in white musical shows.”

Broadway Dance and Death Threats

But it’s uncertain if she ever appeared in the Follies. She did arrive in New York in 1922 and appeared in a variety of shows around town.

But it’s uncertain if she ever appeared in the Follies. She did arrive in New York in 1922 and appeared in a variety of shows around town.

She was cast in the 1923 Broadway musical Jack and Jill, although critics did not take her especially seriously. One described her as “an Egyptian of to-day,” billed as “‘a disciple of King Tut’, and who, it is said, ‘will wear a costume that will call for ‘tut, tut.'”

In May 1924, she joined Michio Itō and Stella Bloch in a special program of Asian dances under the auspices of the Dancers’ Guild in New York – a showcase of intercultural dance art then emerging in the city’s modern dance scene.

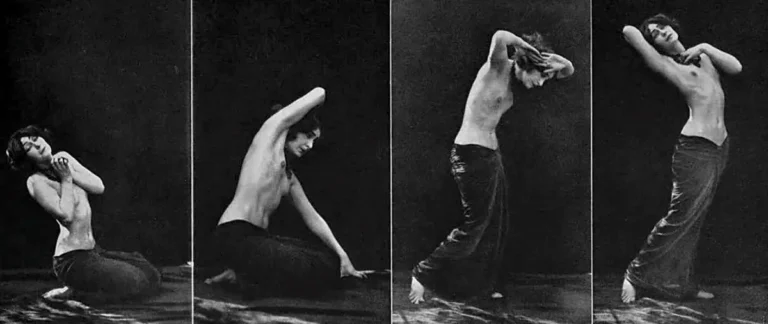

Mindful perhaps of the value of publicity, Inyoka was quoted in a June 1, 1924, Buffalo Times story that she feared returning to India, “her native land,” because mysterious people threatened to kill her. She appears in multi-photo spread with sensationalist questions such as “Has the baring of her body, in her Brahmanic [sic] and Buddhistic [sic] dances, stirred the wrath of Kali, the terrible goddess of destruction?”

Choreographing Oriental Dance

Collaborative Research

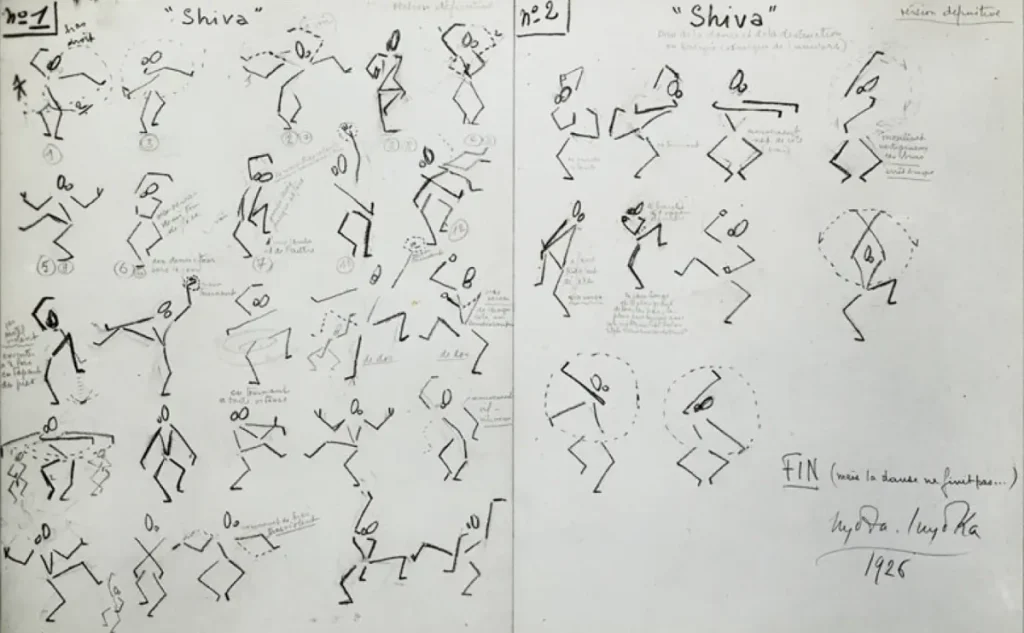

Unlike many contemporaries dabbling in Orientalist themes, Inyoka grounded her “reconstitutions” in rigorous research. She became a familiar figure in the reading rooms of Paris’s great institutions—the École du Louvre, the National Library of France, and the Musée Guimet. She studied ancient texts on dance and performance and examined sacred carvings from temples across Asia. She also collaborated with a number of scholars, including the prominent historian of India, Ananda Coomaraswamy.

The Coomaraswamy-Bloch Circle

In developing her dance Shiva, Inyoka also worked closely with Coomaraswamy’s wife, dancer Sella Bloch, who was one of the six “Isadorables” in Isadora Duncan’s company. The relationship of Inyoka with Coomaraswamy and Bloch has been described as “a pleasure-filled intellectual ménage à trois.”

Exoticism, Indian Dance, and Sacred Energy

Movement and the Quest for the Ancient

Inyoka’s sense of authenticity came not from exact historical detail, but from the spiritual depth and careful structure of her work. Like Sent M’Ahesa and Ruth St. Denis, she performed antiquity as a dreamscape, but where others often offered arty spectacle, Inyoka intended dance to summon spiritual ideas through the body. Inyoka’s unpublished treatise Clef des attitudes et du geste esthétique outlined a theory of gesture as a symbolic language—one that could align the body with eternal principles through specific movements. Her notebooks, filled with diagrams and reflections—such as the “Spiral of Emergence,” mapping creation onto a Fibonacci-like curve—reveal a choreographer who approached movement as a quest for ancient sacred energy.

Colonialism, Race, and the Critic

This spiritual ambition was inevitably filtered through the lens of race and colonialism. French critics lauded her as a “mystic pearl,” a “dusky priestess,” a “seeress of lost rites,” praising her elegance and mystery. Yet, this praise was often laced with exoticizing language that simplified her art.

Her movement was deemed elegant because it was foreign; her ideas fascinating because they seemed ancient. Her visibility was paradoxical: celebrated for inhabiting the Orientalist fantasy structure, even as her artistic intentions were much larger. She was allowed to perform Indian cosmology partly because her mixed heritage seemed to fit a visual mold, confirming rather than disrupting European expectations.

Archives and Preservation of an Artist

Postwar Decline

By the 1950s, the cultural landscape shifted as the post-war European appetite for exotic spectacle waned. Inyoka’s notion of the sacred body fell out of fashion. Inyoka continued to choreograph and teach. She also continued to refine her Clef des attitudes et du geste esthétique, meticulously recording her own creative process. But she was well out of the limelight.

Archival Reawakening and Lasting Legacy

She died in Paris in 1971. There was no major obituary, no grand retrospective. Her name gradually dropped from surveys of modern dance, displaced by artists who fit more neatly into established nationalist or avant-garde narratives. Her costumes, notes, photographs, and performance records were donated to the French National Library, where they have received a good deal of recent attention from scholars.

Inyoka’s legacy isn’t just historical—it’s artistic at its core. She asked what a movement could mean, blurring the line between research and creation, between history and the living body. Now, as scholars and artists return to the fragments she left behind, her trail shimmers again—not only as spectacle, but as an invitation to see dance as more than entertainment.

For Inyoka performance was also a way to honor something deeper that connects movement, memory, and the human experience.

Sources used for this post:

- Heiter, Garrit Berenike. “Egyptologist Dancers – Re-Enacting ‘Ancient Egyptian’ Dances at the Beginning of the 20th Century.” In Textiles in Motion: Dress for Dance in the Ancient World, 224. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2023.

- López Arnaiz, Irene. “Living Archive. Nyota Inyoka’s Archive: Traces of the Ephemeral and Ancient Dances Reenactment.” Anales de Historia del Arte 32 (July 14, 2022): 327–50. https://doi.org/10.5209/anha.83074.

- Project Nyota Inyoka. Border-Dancing Across Time. The (Forgotten) Parisian Choreographer Nyota Inyoka, her Œuvre, and Questions of Choreographing Créolité. https://project-nyota-inyoka.net/.

- Warren, Vincent. “Yearning for the Spiritual Ideal: The Influence of India on Western Dance 1626–2003.” Dance Research Journal 38, no. 1–2 (2006): 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767700007403.

- Chatterjee, Sandra, Franz Anton Cramer, and Nicole Haitzinger. “Remembering Nyota Inyoka: Queering Narratives of Dance, Archive, and Biography.” Dance Research Journal 54, no. 2 (August 2022): 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767722000183.

- Cramer, Franz Anton, and Sandra Chatterjee. “Nyota Inyoka, Biography, Archive: On the Research Project ‘Border-Dancing Across Time.’” Accessed February 28, 2025. https://perfomap.de/map12/decolonial-perspectives/nyota-inyoka-biography-archive.