Prostitution History: Baltimore’s Shocking Hidden Sex Trade in 1916

Revised March 26, 2025

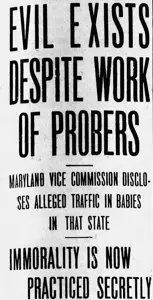

I came across a brothel scandal while researching my historical mystery novel, Into the Suffering City, set in 1909 Baltimore. The Maryland Vice Commission exposed the scandal in 1916. The Commission conducted considerable research into prostitution as it existed in pre-World War I Baltimore and prepared several reports. But, for reasons discussed below, the full findings were never published.

Prostitution History: Hundreds of Sex Workers Interviewed

The reports, full of detailed information about all aspects of the sex trade, deeply embarrassed city leaders. Hundreds of sex workers (or “soiled doves” as they were known) were interviewed, and there is substantial information about the complicity of businesses, the police, and other elements of the municipal establishment. In looking at the reports, one can only conclude that prostitution was thriving, widespread, and deeply entrenched in Baltimore, as it was elsewhere.

This information is pure gold for anyone interested in prostitution history connected with an early twentieth-century American city. Many women are quoted about their reasons for getting into “the life,” and a novelist is hard-pressed to match their words. “Hustled and entered a house because the streets were cold.” “I lived for some time with an actor, who induced me to go into the life.” “Went wrong at 17, then left home and got a room, then entered the life.” “I was born crooked.”

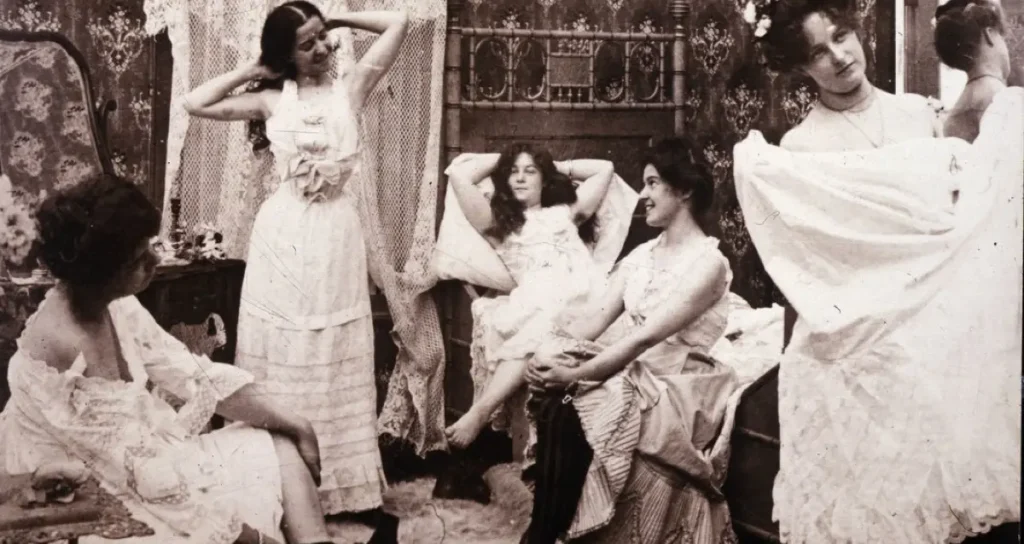

Rich detail is also available about how and where sex workers plied their trade. Bordellos played an important role, but so did saloons, entertainment districts, and “houses of assignation” (short-term rental rooms).

The reports also reveal much about the contemporary professional elite’s attitudes regarding race, class, gender, and perceived levels of intelligence. Commission researchers were among the early ranks of social work and public health professionals, and they strived for an objective, scientific perspective. A modern reader, however, can detect bias.

The Progressive Era: Social Activism

The Progressive Era in America (roughly 1896-1920) featured energetic social activism focused on political and social improvement. Conditions of urban life were of particular interest, including poverty, public health, labor practices, and consumption of alcohol and other drugs.

The Progressive Era in America (roughly 1896-1920) featured energetic social activism focused on political and social improvement. Conditions of urban life were of particular interest, including poverty, public health, labor practices, and consumption of alcohol and other drugs.

A significant category of reform centered on prostitution. From about 1910 to 1919, localities across North America studied the nature and extent of “vice”—commercialized sex—within their boundaries. Big cities such as Chicago, New York, St. Louis, and Philadelphia formed vice commissions, as did smaller jurisdictions including Lexington, KY; Bridgeport, CT; and Nelson, British Columbia. Altogether, over thirty-five localities issued reports across the US and Canada. The studies typically found a thriving sex trade, along with attendant issues like venereal disease, police corruption, and children conceived out of wedlock. Up to this point, many jurisdictions had a history of tolerating prostitution. The work of the vice commissions led to a public outcry and swift outlawing of the practice across North America.

Jurisdictional vice reports relied upon practices developed in the new fields of sociology, social work, and public health. Trained researchers gathered data through interviews with various players in the sex trade, compiled case histories, collected statistics, and drew upon related studies. The intent was to examine the issue from a scientific perspective to provide a rational basis for improved civic governance.

While Progressive Era reformers pioneered modern survey and research methods, they also had views of morality and social worthiness that now appear biased. Many reformers regarded prostitution—the “social evil”— as inherently wrong, and the vice reports contain moral judgments about individuals involved in the sex trade. To modern eyes, the reports are also shockingly insensitive to matters associated with race, gender, and social class.

Houses of Prostitution and Geographic Segregation

As with many American cities, Baltimore authorities tolerated “bawdy houses” in a limited number of specified locations. This practice was known as segregation, and the locations were “segregated districts.” By the second decade of the twentieth century, segregation—and official toleration of the sex trade—fell out of favor. In 1914, before the Maryland Vice Commission reported to the governor, “all known brothels in Baltimore had been shut down by local authorities and their occupants driven into the streets or out of the city.”

The Maryland Vice Commission

Governor Phillips Lee Goldsborough established the Maryland Vice Commission in 1913 to “examine into the conditions of vice in this State and its relation and effect on the community at large.” The commission’s work focused mainly on Baltimore.

Dr. George Walker, an eminent Johns Hopkins Hospital surgeon and public health advocate, served as chairman. Among the fourteen other members were Dr. J.M.T. Finney, a prominent Johns Hopkins surgeon and public health proponent; Anne Herkner, of the Maryland Bureau of Statistics; Louis H. Levin, of the Jewish Charities of Baltimore City; and Dr. Lillian Welsh, a physician and early promoter of public school health and hygiene education.

The commission’s work reflected the era’s professional standards for social research and fact-finding. Undercover operators documented hundreds of meetings with unsuspecting madams, clients, prostitutes, and others tied to the sex trade. Commission reports are replete with valuable quotes, details, and tabulated data. The accounts provide a rare glimpse into the lives and circumstances of people otherwise forgotten by history.

Commission Reports

The Maryland Vice Commission officially submitted five reports to the governor during late 1915/early 1916:

- “Commercialized Vice “(sex-for-money, involving madams, bordellos, and streetwalkers).

- “Clandestine Prostitution” (adultery, predatory sex in the workplace, and women exchanging sex for gifts).

- “Places of Assignation” (locations used for illicit sex, including hotels, saloons, dance halls, and moving pictures).

- “Immorality in Baltimore County, Anne Arundel County”, and

- “Traffic in Babies” (sale and disposition of illegitimate babies; published as Traffic in Babies: An Analysis of the Conditions Discovered During an Investigation Conducted in the Year 1914.

Only the fifth report was ever published. The four unpublished reports exist in their original typescript form on the shelves of the Enoch Pratt Library’s Maryland Department in Baltimore.

Reaction to the Commission Reports: Brothel Scandal? What Brothel Scandal?

Preliminary release of the reports caused a sensation. Leading citizens struggled to accept the catalog of details involving commercialized prostitution. Worse still were the reports on “Clandestine Prostitution” and “Places of Assignation,” which outlined the common practice of successful men keeping mistresses and seducing women who worked for them as stenographers, switchboard operators, and salesgirls, among other occupations.

Some essentially claimed the report was “fake news.” Mayor James Harry Preston immediately denounced the findings, telling the Baltimore Sun the reports were “a scandalous libel on life in Baltimore.”* A rival organization, “The Society for the Suppression of Vice,” declared Baltimore “is now one of the cleanest cities in the country and that moral conditions are better now than they have been for years.” Another excitable observer claimed the report “[stripped] the clothes off” the city, leaving it “naked and exposed.”

There is no evidence, however, to suggest the reports were anything but authoritative, accurate, and completely credible.

Some authorities took the Vice Commission reports seriously and wished to use the research to punish offenders. A grand jury summoned the commission chairman, demanding names of those interviewed in the study with an intent to prosecute. The chairman refused to disclose the names, and the matter ended, despite the “several grand jurors . . . [who] wanted to have Dr. Walker committed for contempt in refusing to answer questions.”

Opposition to the findings was so intense that the commission never published four of its five reports. This put Baltimore in rare company, as dozens of other localities dutifully published their findings.

Some reformers refused to let the issue fade from view. Dr. Howard A. Kelly, a prominent Johns Hopkins Hospital doctor and teetotaling moral crusader, led the charge. After the city blocked publication of the reports, Kelly printed a scathing condemnation entitled The Double Shame of Baltimore: Her Unpublished Vice Report and Her Utter Indifference. “Vice in low theatrical shows and sex immorality is literally eating the heart out of our city life,” he wrote. “For the first time in her life, Baltimore has gazed into a clear glass and beheld her natural face.”

Double Shame further declared, “Apparently Baltimore did not know that she had a body of flesh and blood and weakness . . . the discovery has been too much for her.” Many “supposedly respectable” citizens, including men “in high station,” were sexual predators. “Many girls—young, pretty, fresh—[were] subjected to undue pressure from employers and male employees.” Such men were supposedly upstanding “people whom nobody knew to be immoral.”

Controversy Fades

Controversy over the reports receded quickly. After a flurry of articles in late 1915 and early 1916, a search of the Baltimore Sun newspaper index reveals next to no subsequent references to the Maryland Vice Commission. An exception is the 1937 obituary for Dr. George Walker, which credited his chairmanship of the Commission.

Controversy over the reports receded quickly. After a flurry of articles in late 1915 and early 1916, a search of the Baltimore Sun newspaper index reveals next to no subsequent references to the Maryland Vice Commission. An exception is the 1937 obituary for Dr. George Walker, which credited his chairmanship of the Commission.

Prostitution continued to flourish in Baltimore. “The Block,” a downtown entertainment district near the central police station, grew into a world-famous collection of “strip bars and burlesque houses that offered men more than just a strip-tease.” The area’s heyday took place during the 1950s when entertainer Blaze Starr gained national attention from an article in Esquire entitled “B-Belles of Burlesque: You Get Strip Tease With Your Beer in Baltimore—No Cover Charge, of Course”. Subsequent years witnessed a precipitous decline in The Block’s fortunes, but as late as 2003 Baltimore had a reputation for “its ready availability and affordability of its prostitutes.”

The First Commission Report: “Commercialized Vice”

Section two of my book reproduces the original Maryland Vice Commission’s first report, “Commercialized Vice.” The document is a treasure-trove of primary source material for the history of prostitution and many other topics relating to social history, including accounts of and tabulated data for:

- Social conditions contributing to prostitution.

- Specific accounts of life in bordellos and other locations used for prostitution.

- Individual earnings for prostitutes as compared to earnings from previous employment.

- Procurement of prostitutes from neighborhoods, department stores, and amusement resorts.

- Prostitute use of drugs and alcohol.

- Accounts of prostitute sexual sensation.

- Details about the incidence of venereal disease (including percentages of women examined found to have syphilis and gonorrhea).

- Demographic details for prostitutes (age, family, religion, nationality, physical description).

- Descriptions of patrons (“johns”).

- Price gouging arrangements between madams and merchants to overcharge prostitutes for clothing and accessories.

- Separate details for “streetwalkers,” including analysis of 220 women.

- Specific accounts of how prostitutes seek and acquire customers.

- “Sexual perversion (Homo-Sexuality)” in schools, among women, among men.

- Review of prostitution-related issues in other American cities and foreign countries.

An Invaluable Source Document for Prostitution History

The Maryland Vice Commission reports offer a glimpse of Baltimore life during the early Twentieth Century that is exceedingly rare. Prostitution was far too “improper” to be covered in detail in anything but an analytical report, and even that form proved too controversial. History owes a debt of gratitude to the Maryland Department of the Enoch Pratt Library for preserving these documents.

This post is drawn from my book Prostitution and Illicit Sex in Baltimore: Commercialized Vice, Report of the Maryland Vice Commission, 1916.

For a bit more background on the report, see this background post.