Salome Dance: Scandalous But High-Minded

In early 20th-century performance, art dance emphasized expressive movement, innovation, and aesthetic depth, as seen in modern dance and ballet. Erotic dance focused on sensual display and physical allure, often for popular entertainment. Art dance sought cultural legitimacy; erotic dance catered to titillation, though the boundaries often were blurred, especially when it came to Salome dances.

Belly Dance Sets the Stage for Salome Dance

The World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 Chicago introduced the public to belly dancers supposedly from the mysterious “Orient” (at least one was from New Jersey). A number of belly dancers were billed as “Little Egypt” and one, Ashea Wabe, became front-page news in 1896 after she was supposedly to dance nude at a swank New York City bachelor party.

Anthony Comstock, a crusading government inspector, branded the belly dance as indecent and tried, without success, to suppress it.

The dance, known in French as danse du ventre, was so popular that cabarets soon offered performers doing a variant known as the hoochie-coochie (Also spelled hootchy-kootchy, along with many other variations).

Loie Fuller as Salome

In 1895 Paris, American Loie Fuller was among the first to present a Salome dance which drew upon elements of how the west imagined the Orient. Famous for her skirt-swirling “serpentine dance,” Fuller’s Salome failed to impress critics who found her performance devoid of a necessary “aura of unreality, ineffability, and mystery.”

Fuller reprised Salome in 1907 Paris, dancing to Florent Schmitt’s ballet Tragédie de Salomé. Reviews were lukewarm, although the Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique wrote: “Under colors of various lights … in which she seems to swim like in a fluid, the dancer of charm and grace, waving supple arms and fast legs, evolves sometimes with languor, sometimes with violence, always in fair and harmonious rhythms.”

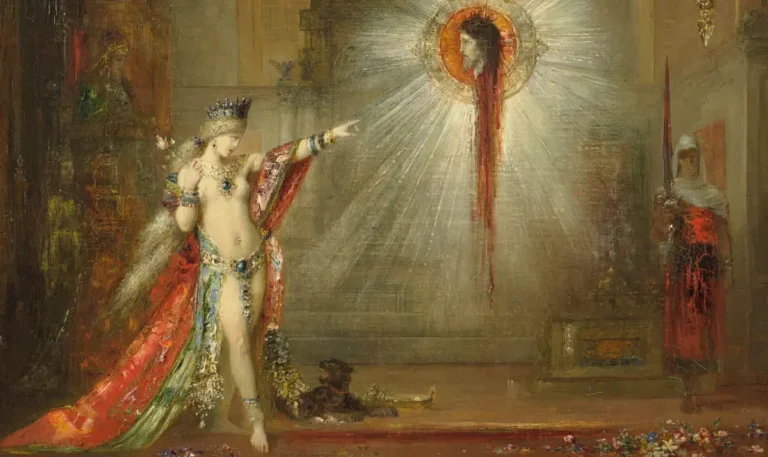

Maud Allan and the Vision of Salome

A self-taught Canadian dancer, Maud Allan, raised Salome dance to a fever pitch after her 1908 London debut, dancing barefoot to a musical composition, Vision of Salome. Allan is now largely forgotten, a fate that seemed unimaginable at the height of her fame. At the time of Allan’s 1908 triumph, Isadora Duncan was the best-known practitioner of what was known as barefoot dance.

Duncan pioneered “art dancing,” a style apart from the conservative strictures of classical ballet. Dressed as a Grecian goddess in a flowing toga, she danced with startling freedom and expressive variety. She drew mixed reactions. Critics debated her artistic merits; some saw her as brilliant and transformative, while others dismissed her as a crackpot.

Maud Allan had things going for her that Duncan did not. King Edward VII had previously endorsed Allan’s dancing with great enthusiasm after a private show. The king had enormous influence among the fashionable London elite, and his stamp of approval automatically put her in demand. Allan also danced in an erotic “Salome costume” of beads and sheer fabric, drawing upon the popularity of the exotic Orient in general and Strauss’s opera in particular.

Allan’s performance drew a rapturous response from many. One reviewer piled on the purple prose:

Her naked feet, slender and arched, beat a sensual measure. The pink pearls slip amorously about her throat and bosom as she moves, while the long strands of jewels that float from the belt about her waist float languorously apart from the sheen of her smooth hips . . . The desire that flames from her eyes and bursts in hot gusts from her scarlet mouth infect the very air with the madness of passion. Swaying like a white witch, with yearning arms and hands that plead, Maud Allan is such a delicious embodiment of lust that she might win forgiveness for the sins of such wonderful flesh. [As Salome, she twists] her body like a silver snake eager for its prey, panting with hot passion, the fire of her eyes scorching like a living furnace.

Fame, Scandal, and Oblivion for Maud Allan

While Allan was not a political rebel, she served as a change agent. Petra Dierkes-Thrun writes: “As Salomé, she also inhabited a dangerously assertive and forceful femininity . . . [some] identified Allan as a feminist and as an artist whose Vision of Salomé encouraged ladies and ordinary women to break codes of modesty in clothes and behavior at a time when the suffragettes were marching in the streets.”

Others judged her act less favorably from an artistic standpoint. In The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, Max Beerbohm observed that Allan did not convey much, if any, lust. “I cannot imagine a more lady-like performance,” he wrote.

Beerbohm went on to say that “Some six or seven years ago, there arrived in London a certain Miss Isidora [sic] Duncan . . . who did not succeed in obtaining a public engagement.” Noting that Duncan had originated the style, he writes that those who have seen both perform agree “that Miss Allan’s dancing is by far the less remarkable.” That Allan succeeded where Duncan did not “is as an amusing instance of the power of mere fluke in human affairs.”

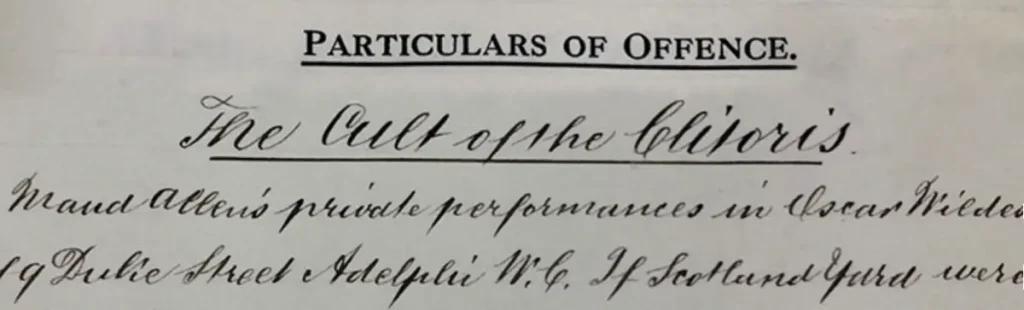

Whatever the merits of Allan’s dancing, her fame was brief. Her popularity was already in decline when, in 1918, an English gadfly accused her of membership in “the cult of the clitoris.” This odd phrase was an oblique reference to lesbianism, and Allan sued for libel. But, like Oscar Wilde twenty years before, she lost in court and quickly faded into obscurity.

The Mystery of Adorée Villany

Europe generally had a more tolerant view of how much skin a dancer could show. But the enigmatic Adorée (or Viola) Villany—who was either French (born in Rouen), Hungarian (“The Pearl of the Puszta”), or a German Jew (born in Danzig as Erna Reich)—pushed the limit with nudity on stage.

The Grazer Volksblatt states she began performing in the Berlin Überbrettl cabaret (perhaps in 1902) as “a Duncan imitator.” Karl Toepfer writes that she first came to public notice in 1905, performing the Dance of the Seven Veils ending completely unclothed while speaking Salome’s final monologue from Wilde’s play.

In 1911, Munich police arrested Villany, now known as “Nackttänzerin” (nude dancer), for indecent exposure after various exotic dances, including one as Salome. Villany defended herself as a “reform dancer,” claiming “my unveiled body reveals my soul.” Various artists came to her defense, and a jury acquitted her based on “the higher interests of art.”

Villany wrote in 1912 that hers was the only authentic Dance of the Seven Veils, as she performed it as “Huysmans dreamed, as Regnault painted, and as Oscar Wilde imagined.” She denounced other interpretations as “tame Salome dancers” who showed “thoughtless movement” by confining “their emotions into squiggly pirouettes.”

Villany appeared quite often in the German press from about 1911 to 1914, but I found no mention of her after 1927.

A Ziegfeld Follies Salome

Mademoiselle Dazie (Daisy Ann Peterkin) danced as Salome in Florence Ziegfeld’s “Follies of 1907” (the first installment of what would become the long-running Ziegfeld Follies) before Maud Allan conquered London. Dazie, who was originally known as “La Domino Rouge” for the red mask she wore on stage, had the distinction of presenting one of the first Salome dances in America; the interpretation was just one part of her act, which also included “The Jiu-jitsu Waltz” and “The Living Doll Dance.”

Dazie’s biggest contribution to Salomania was opening a “school for Salome” that, by the summer of 1908, launched around 150 new Salomes every month.

Mata Hari Channels Salome

Dutchwoman Margarethe Zelle achieved huge success in 1905 Paris billing herself as a Javanese princess named Mata Hari. She wore a revealing costume while claiming to perform “sacred Hindu dances.”

Mata Hari was commonly associated with the Jewish princess, so much so that she felt entitled to dance in a production of the Strauss opera Salome, claiming “Only I will be able to interpret the real thoughts of Salome.”

Unsuccessful in convincing Strauss (by most accounts, she was not an especially talented dancer), Mata Hari’s fame soared as she performed with fewer and fewer clothes. She originally began wearing a flesh-colored body stocking under her costume but soon discarded it in favor of her own skin.

With her star fading during World War I, Mata Hari became entangled in an absurd espionage plot, and was arrested. A French firing squad executed her in 1917 based on the flimsiest of evidence. Tragic though her death was, it ensured her enduring fame as the personification of the seductive femme fatale.

Ida Rubinstein: A Naked Salome in Czarist Russia

The Russian actress and dancer Ida Rubinstein also broke the rules of decorum. She started in 1908 Saint Petersburg, performing as Salome in Wilde’s play. Rubinstein also staged the Dance of the Seven Veils as a separate show, in which she reportedly danced naked.

Tall and boyishly thin, Rubinstein made a striking visual impact on stage. She came to the attention of Sergei Diaghilev, manager of the Ballets Russes. Despite Rubinstein’s limited formal training, she danced in several Ballets Russes productions. She performed as Salome on multiple occasions, including in Florent Schmitt’s Tragédie de Salomé with the Paris Opera in 1919.

Natasha Trouhanova, Tamara Karsarvina, and the Ballets Russes

Schmitt reworked his 1907 version of Tragédie de Salomé, cutting its length in half and intensifying the music and choreography. Apart from Rubinstein’s performance, memorable stagings of the revised ballet (sometimes termed a “mute drama”) took place in 1912 and 1913.

The 1912 Paris production of Tragédie de Salomé starred prima ballerina Natasha Trouhanova. She drew praise for her beauty and graceful movement, which “softened everything into Venus.”

Tamara Karsarvina and the Ballets Russes staged Schmitt’s work again in Paris the next year. Despite sets and costumes that conjured “a spectacular Art Nouveau aesthetic,” most critics regarded the show as an overly experimental flop. One reviewer, however, found Karsarvina “a majestic Salome” with “extraordinary qualities of grace, lightness and power.”

Ruth St. Denis: “Out-Saloméing all the Salomés”

Salomania also figured in the life of modern dance pioneer Ruth St. Denis. An interpreter of Eastern dance, St. Denis performed in Salome-mad 1909 New York City. According to Elizabeth Kendall, St. Denis, “whose commercial instinct never failed,” wore “Salomé’s jeweled harness” and inspired one newspaper reviewer to proclaim “Out-Saloméing all the Salomés, Miss St. Denis burst upon dazzled audiences.”

Late in her life, St. Denis choreographed and danced as Salome. The Los Angeles Times quoted her concept of Salome as: A child-woman, a young girl just beginning to be aware of her body but enough of a child to lose herself in the fantasies of games. Her dance involves imaginative transformations into various creatures—a peacock, a butterfly—to beguile Herod’s mind as well as his senses.

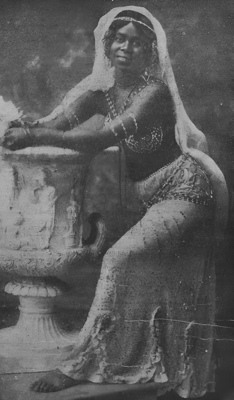

Aida Overton Walker and A Black Salome

In 1908, Aida Overton Walker, a versatile singer, dancer, and choreographer, did a Salome dance as part of the “Bandanna Land” musical revue at New York’s Grand Opera House. She reprised the performance in 1912 on Broadway at the Victoria Theatre.

Walker avoided the overt eroticism that others brought to the dance, and claimed her Salome was more artistic than erotic, more spiritual than sensational.

Reviewers concurred, with one observing that Walker “was clothed more than several of the other local Salomes” and “relied on the grace of her dancing for effectiveness.”

Afro-Cuban Dancer La Perla Negra and Visión de Salomé (Cuchipanda)

The Belgian ballerina Felyne Verbist also danced as Salome. Verbist was among the first European prima ballerinas to visit South America, and she may have influenced the Afro-Cuban dancer Dulce Maria Morales Cervantes (in Spanish) stage name La Perla Negra. In 1913, Morales moved to Valencia, Spain, to perform cakewalks, classical dance, and rumbas.

La Perla Negra’s repertoire also included “Visión de Salomé (Cuchipanda).” As Kiko Mora explains, “cuchipanda” is a dance related to tango, rhumba, and fandango. Morales’s Salome interpretation was a remarkable blend of Orientalist dance and contemporary Afro-Cuban dance.

Morales was hugely popular upon her arrival in Spain and, according to Mora, was “The first Afro-American to perform on a Valencian stage and, quite possibly, the first in the entire country in the 20th century.” Morales is also notable for bridging multiple styles, including authentic Cuban dance (such as the rhumba), the Spanish variety-show version of Cuban dance, and avant-garde modern dance.

Vera Fokina and Mikhail Fokine Present Salome

Theatrical interpretations of Salome continued to evolve after World War I. During 1919–20, ballerina Vera Fokina performed as Salome in Europe and America. The New York Daily News hailed her performance as “closely approximating genius” as well as “poignant and subtle.”

Fokina’s husband, dancer and choreographer Mikhail Fokine, originally developed the ballet for Ida Rubinstein and the Ballets Russes.

1920s Berlin and Radical New Salomes

During the 1920s, Weimar Germany hosted radical new Salome dances, including Anita Berber’s nude interpretation. Karl Toepfer states Berber began her Salome dance from “a huge urn filled with blood.” After “panting orgasmically,” she executed several expert ballet steps before finishing with a crawl back into the urn.

Berber declared that “If everyone had a body like me, everyone would walk around naked.” She was infamous for her open bisexuality, drug use and outrageous behavior. “She needed scandal like her daily bread,” wrote her contemporary Klaus Mann. “Post-war eroticism, cocaine, Salomé, ultimate perversity—such were the terms the mirage of her glory was made of.”

Berber reveled in her shock value, and reportedly hung about Berlin nightspots naked except for a sable wrap, a pet monkey, and a silver container filled with cocaine. The revels did not last long, as she died at age 29. Most sources cite tuberculosis as the cause, although there was a rumor that she died amongst used morphine syringes. According to Mel Gordon, Berliners were by then tired of her antics and she died a “carrion soul that even the hyenas ignored.”

In 1923, the German dancer and actress Valeska Gert presented a starkly different version of Salome. Gabriele Brandstetter describes it as: “A new, grotesquely shrill method of representing the physical femme fatale image. In a radically alienated, ruthlessly garish performance, the beautiful, exotic-attractive art nouveau Salome was presented as an outdated cliché of femininity.”

Gert danced without music, with women rhythmically howling offstage. Distinct from earlier Salome portrayals, she wore only a simple dress rather than an exotic costume. Critics described Gert as “a master of . . . psychological caricature” and her performance as “simultaneously supremely animalistic and supremely divine.”

This post is part of a broader exploration of Salomania and Salome’s rise as a cultural icon in the early 20th century.

→ Visit the main Salomania hub page to discover more.